WWII:

The Internment of Japanese Canadians

Prisoners in their own Country

From 1942 to 1949, Canada forcibly relocated and incarcerated over 22,000 Japanese Canadians—comprising over 90% of the total Japanese Canadian population—from British Columbia in the name of "national security". The majority were Canadian citizens by birth and were targeted based on their ancestry. This decision followed the events of the Japanese Empire's war in the Pacific against the Western Allies, such as the invasion of Hong Kong, the attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, and the Fall of Singapore which led to the Canadian declaration of war on Japan during World War II.

Similar to the actions taken against Japanese Americans in neighbouring United States, this forced relocation subjected many Japanese Canadians to government-enforced curfews and interrogations, job and property losses, and forced repatriation to Japan.

1939

1941

December 7

1941

December 8

1941

December 18

1942

January 14

1942

March 4

1945

September 2

1949

April 1

1988

September 22

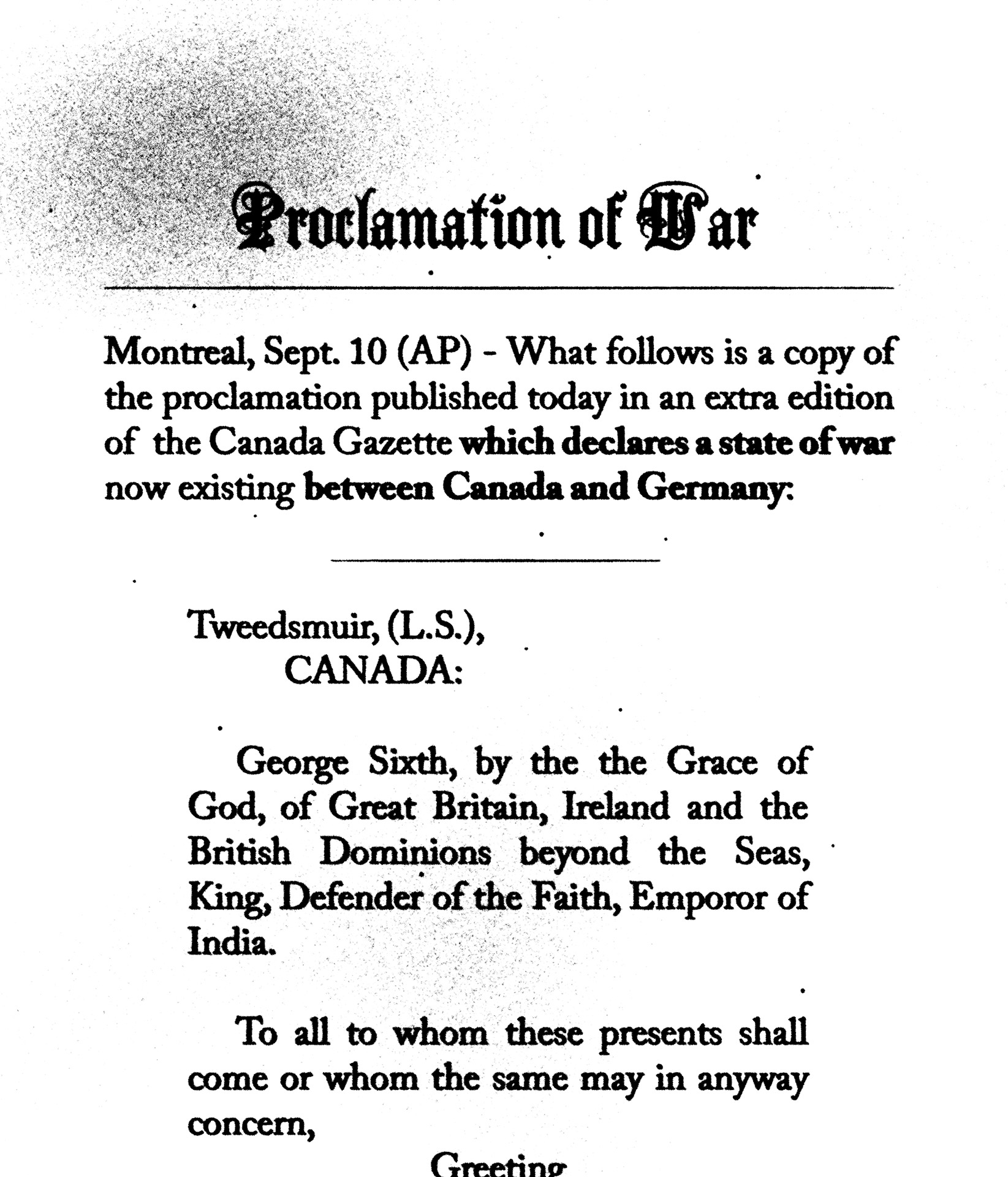

Canada entered WW2 in 1939, one week after the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. Even though Canada was required by the UK to enter the war, Prime Minister Mackenzie King decided to wait a week to signify Canada’s independence.

December 7th, 1941

Japanese forces attacked the naval base at Pearl Harbour in Hawaii.

Pearl Harbour Under Attack

December 8th, 1941

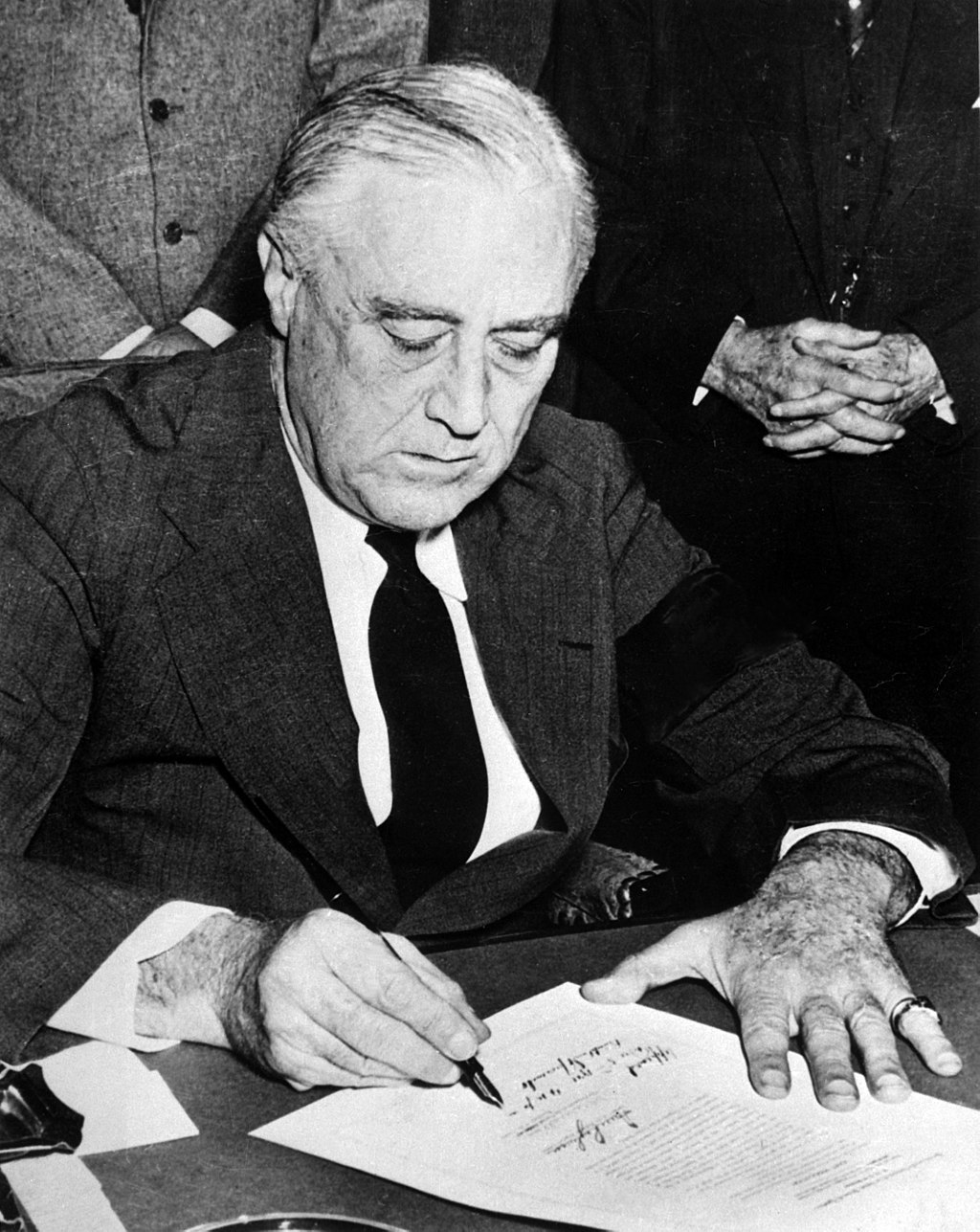

On December 8, 1941 the United States and Canada declared war on Japan. The US president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, addressed the senate to announce that the United States was declaring war on Japan following the attack on Pearl Harbour.

US President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs the declaration of war.

December 18th, 1941

On December 18, 1941, Japanese forces overran the Chinese city of Hong Kong. Two thousand Canadian soldiers who were stationed there were captured or killed. When news of this reached home, many Canadians regarded their Japanese Canadian neighbours with suspicion. They believed they could become spies for the Japanese military, even though Canada’s top generals and the RCMP did not believe it and there was never any evidence to suggest that it ever happened.

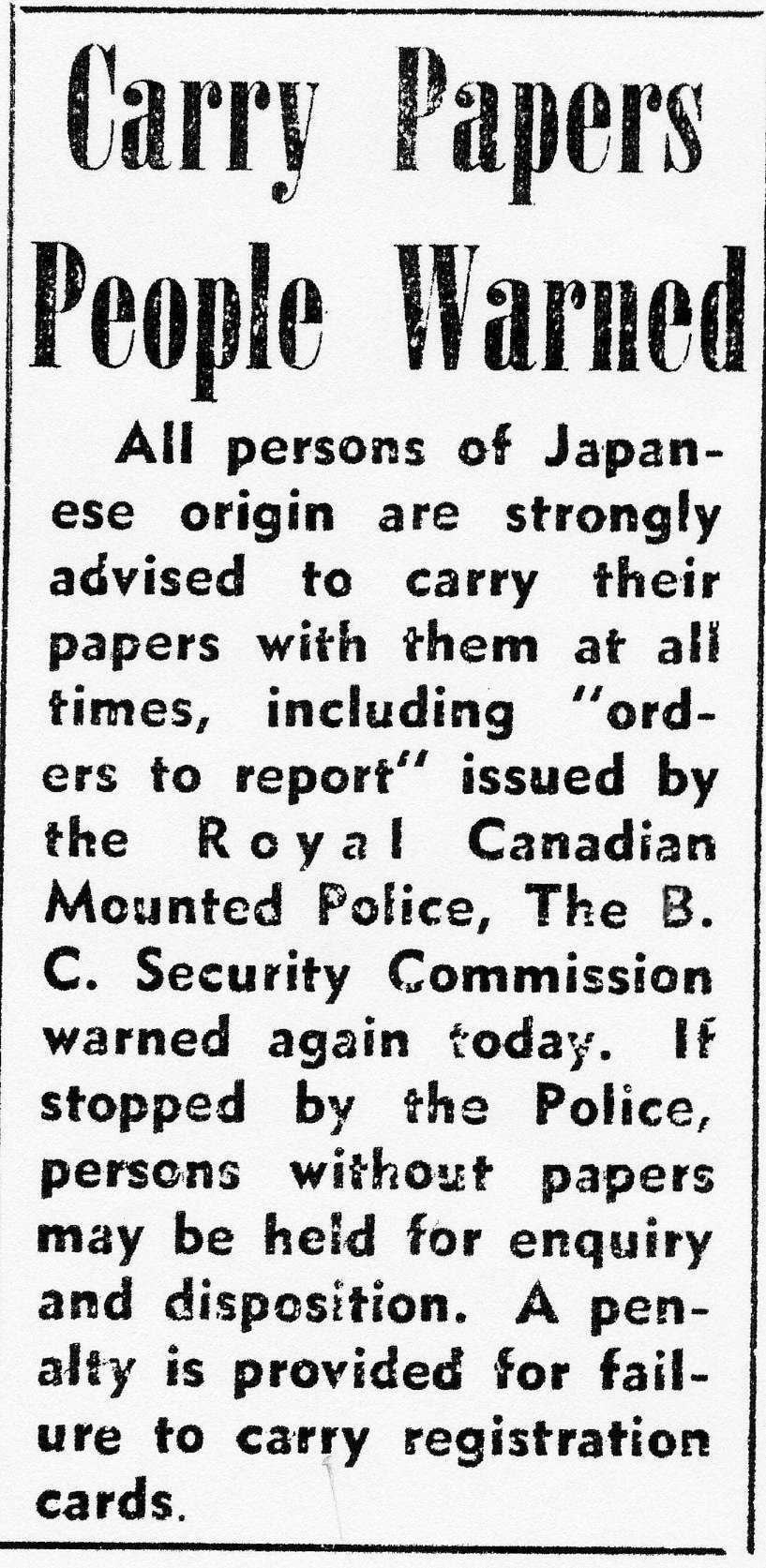

Notice to Carry Papers

At the time, most Japanese Canadians were living in British Columbia. Within a matter of days, the Canadian Pacific Railway fired all of its Japanese employees, and other industries did the same thing. Japanese fishermen in Vancouver were not allowed to fish anymore and the Canadian navy seized 1,200 fishing boats.

January 14th, 1942

On January 14, 1942, the government declared that all land within 100 miles of the BC coast was now a “protected area” and that all Japanese men of fighting age were to be sent to camps inland where they would work on road crews.

Notice to All Males

March 4th, 1942

Then, on March 4, 1942, the government decided that ALL Japanese Canadians had to leave the “protected area”.

They were told to pack one suitcase each with all the belongings they could carry. The rest of their property, their cars and their houses and land they owned, were seized by the government and held in “custody”. Eventually, these were sold at cheap prices to pay for the camps. Japanese Canadians were now like prisoners of war in their own country.

Japanese family waiting to board a train. Families were forced to leave their homes and possessions behind.

(Source: Used with permission from the Nikkei museum)

At first, most of the Japanese women and children were sent to temporary accommodations in Hastings Park in Vancouver, where they were forced to wait for the trains that would take them to hastily-constructed communities in the BC Interior. Many Japanese families lived for months in stalls that had originally been built for animals.

Eventually, they were packed onto trains and sent to places like Slocan and Lemon Creek.

(Source: Used with permission from the Nikkei museum)

David Suzuki, who was five years old at the time, was sent with his family to a community in the Slocan Valley. He did not understand what was happening.

Approximately one third of the people sent to the camps were kids who were old enough to attend school. Schools were set up for them but they were crowded and did not have enough desks for everyone or textbooks to distribute among the classes.

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Mr. Suzuki recalls living with his family in a tiny room in an old hotel. His family was apparently one of the luckier ones. Even so, the hotel was filthy and infested with bed bugs. Often, he says, he woke up in the morning covered with bites.

Most Japanese lived in hastily-constructed shacks with paper-thin walls and no insulation against the cold in wintertime. Cooking facilities were shared among many families, as were baths and outhouses.

(Source: Used with permission from the Nikkei museum)

On September 2, 1945, Japan formally surrendered. The war was finally over. But the Japanese Canadians who had been living in the camps were not allowed to return home and their property was not returned to them. Instead, they were given a choice: either give up their Canadian citizenship and be deported to Japan or leave their former homes in BC and move to other provinces east of the Rocky Mountains. About 4,000 people chose to go to Japan, which had been all but destroyed by the war. The rest moved to Ontario and Quebec and the Prairie Provinces, where they tried to rebuild their shattered lives.

Then, on April 1, 1949, four years after the war ended, the remaining Japanese who had stayed in Canada were given back their full Canadian citizenship. They could now return to their former homes in BC. But for most, there was nothing left to go back to.

On September 22, 1988, almost forty years later, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney formally apologized to Japanese Canadians for their harsh treatment at the hands of the federal government during World War Two.